What is talent, anyway? That is the question that has been on my mind this past week. And it has been on my mind for a particular reason.

During the day, I have been working on a task that I don’t particularly enjoy. Namely, visual design, also known as the art of not making ugly things.

And… well, I am not very good at it. I am very good at recognizing when design isn’t good, but I have a very difficult time creating good design from scratch.

That isn’t the frustrating part, though. Everybody is bad at something the first time they try it. Some learning curve is expected.

The frustrating part is that I am not getting better. And it isn’t that I haven’t spent the time trying to get better. In the past month, I have spent well over 50 hours working on visual design.

Now, I will grant you that that isn’t a long time. Skilled designers have spent hundreds if not thousands of hours perfecting their craft, and I shouldn’t compare myself to them. I get it. My problem isn’t that I haven’t improved to that level. My problem is that I haven’t improved at all.

The Specific Problem

My failure in visual design comes as no surprise to me. It isn’t as if I think things are going well and only realize too late that they aren’t. Quite the opposite – I feel intense opposition every step of the way. I personally believe my problem is that I don’t have design intuition.

I realized while writing this post that what I think of as intuition is actually what most people would call talent. But I think the word intuition does give a slightly different perspective that closely matches what I am experiencing.

So I think I don’t have design talent, or design intuition. What I mean by a lack of intuition is that the design process itself is not obvious to me. I often find myself asking, “what do I do now? How do I achieve what I am trying to achieve?”

In other words, I don’t know how to get from point A to point C, where point A is usually a blank piece of paper and point C is the finished design. This in itself isn’t a particularly unusual problem. When working on large projects in any field, knowing how much work has to be done before you see the final product is daunting.

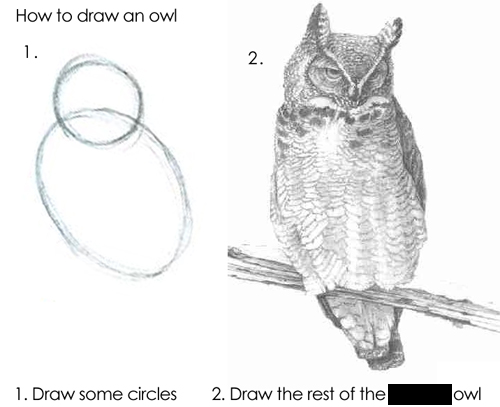

A to C isn’t really my problem, though. My problem is A to B, where B is any step between A and C. In other words, I don’t know how to draw an owl:

This is exactly how I feel when attempting visual design. I know where I start and have a decent idea where I end, but I have no idea what any of the steps in-between are. And I cannot figure out a good way to learn what they are, either. I have no intuition to tell me what comes next, because I am not a talented visual designer.

But I am actually good at other things. At least, I like to think so. I think I am good at writing and programming, at the very least. And my experience with them is much different.

The Power of Intuition

When I am writing, I do know what step comes next. I can make iterative improvements and go from a blank page to a completed blog post. In fact, if you are reading this right now, I was successful.

When I write these posts, it is like I am talking to somebody. And talking is a skill that has a very unique property among other skills.

Everybody can do it. Everybody knows how to talk. You can go anywhere in the world at any point in history, and find that everybody knows how to talk. They may not know how to read or write, but they can talk. And that is because talking is an innate skill – people are literally born with it. You might say they have… intuition.

Think about it. When you are talking, do you really think about what you are saying? Do you think through the choice of every word? Do you think about the flow of your sentences? Not really, right? It kind of just… happens.

How would you even explain talking to somebody? It is such an innate ability that I doubt anybody can explain how they talk. Every explanation would effectively be a form of “you just do it.” Just draw the owl, it isn’t that hard.

There is something very important that we need to note, though. People aren’t born with the ability to speak, they are born with the ability to learn how to speak. People learn to talk incredibly quickly, when you think about it. Compare how well people learn their first (native) language with how well they learn their second. In most cases (in the US), most people completely fail to learn a second language. The difference, I believe, is a lack of intuition. People have intuition when learning their native language, but by the time they try learning a foreign language, the intuition is gone.

People can successfully learn a foreign language. But for many of them, it is difficult.

I think this highlights how much of a helping force intuition is. It is like the difference between biking uphill and downhill.

To be fair, talking isn’t a normal skill and isn’t really a fair example. The human brain literally has speech centers dedicated to the task. And, of course, learning a foreign language is much easier if you are around it constantly. At least, that is what I hear – I am one of the dull people who can only speak English.

So speech may not be a realistic example. I think writing is a fair example, though, because that is a learned skill. Not everybody can write, and certainly fewer write well.

My experience with writing is exactly the opposite of my experience with visual design. When I am trying to design something, I don’t know how to progress. But when I am writing, I progress very naturally and hardly think about it.

But for others it is the exact opposite. Somewhere out there are people who can draw owls, but can’t write to save their life. They presumably feel the same lack of intuition when writing that I feel when trying to design.

I know for sure there are some things I am good at and some things I am bad at. And in most cases, it is because I have more or less intuition about that specific thing.

Some Examples

I realized a long time ago that I don’t have what I call physical intuition. I am bad at visualizing how to complete physical tasks. I built a computer a few months ago, and it literally took me almost a full day (let’s say 10 hours) to do it. It isn’t that I don’t know how to build a computer, it is that I just physically have a lot of trouble figuring out how things fit together, despite knowing what every part does.

It isn’t that I can’t learn how to do a specific physical task. Once I learn a physical task – usually with assistance – I can repeat it. For example, the case fans I got for my computer came with these rubber screws. You basically have to pull them through the respective mounting holes, which isn’t intuitive at all, in particular because it seems like they are going to snap when you stretch them that far. In fact, one of them did snap when I did that. And, of course, there were no spares. Such is life, I suppose.

It just wasn’t intuitive to me. You literally pull a little bump on the screw through a hole smaller than it. But because rubber is magic, it actually works… at least, it does when it doesn’t snap. But I didn’t figure that out on my own. I looked up several videos of similar screws to make sure that was, in fact, what you had to do. It probably took me 30 minutes just to do that tiny step.

Now I know how to use rubber screws. But I still don’t have intuition. If I built another computer, I would know how to do the parts I have done before, but I would still have trouble doing anything new, because I don’t have intuition for how it should be done. Intuition impacts learning new things.

Another interesting data point is learning math. Most people seem to struggle quite a bit to learn math. I feel I have a sort of in-between experience learning math. I have always been “good” at math, but I don’t particularly enjoy the process of learning math. At this point, I have taken up to calculus 3 (as well as the cruel and unusual punishment they call discrete math), so at this point it is clear to me that I can learn math if I need to. But it is hard for me to learn math. I got straight A’s in all of these subjects, but I also had no life outside of school and spent my weekends doing math. It wasn’t any natural skill that made me successful, but sheer discipline (and some stubbornness).

I really cannot emphasize enough how hard these classes were for me. I took five courses per semester, and the math courses took at least as much time as the next three courses combined. I once had a take-home discrete math exam with 5 problems. That sounds easy, but it wasn’t. I spent over a day on that exam. Leaving any answer blank would presumably be a 20% deduction. And worse yet, you could not wing these problems. They were all some sort of proof. And when you don’t know how to prove something in math, it is pretty obvious. This particular professor had a habit of introducing new problems on exams that were never covered in class. Challenge problems, I call them. The theory is that if you actually understand the material, you can figure out how to solve the new problems as well using the same concepts. I thought I understood the material, and it still took me quite a while to solve these problems.

The fact that challenge problems exist suggests that most people don’t learn math intuitively. For example, math is usually taught using standardized types of problems. You might encounter a distance-rate-time problem, or a run-of-the-mill trig problem with a lighthouse. And all the problems on the test are the same type of problem with the specific values changed. If you put a type of problem on the test that wasn’t taught before – a challenge problem – most people will not solve it correctly.

When you think about it, challenge problems are really just a particular type of problem that test the ability to learn. They effectively ask “given the concepts you have already learned, can you extrapolate and learn something new?” But learning new math without being taught it is very difficult. The people that do that get their names in textbooks. Newton and Leibniz didn’t learn calculus from a textbook. They effectively wrote the first calculus textbooks. Not only did they learn how to draw the owl, but they did it without any instruction.

But these people (you know, mathematicians) seem… different. Not only do they learn these challenging concepts on their own, but they chose to learn them in the first place. Newton didn’t have to pass a calculus exam to graduate. And yet he invested the time in discovering how it worked.

That is the crucial difference. I believe most people can learn math with discipline and good instruction. But I think almost nobody has the potential to expand the field and do something truly innovative – because they aren’t driven. They aren’t obsessed with math. And, I suspect, because they don’t have intuition.

Even More Examples

You thought I was done? Nope, just getting warmed up. But I know you have that goldfish attention span, so I threw in another header just to keep you on track.

In fact, I only listed two examples so far. The math one was just really long, possibly because math is hard and I like ranting about that fact. But let’s continue.

I play chess. You know, that game that isn’t checkers that has horses and stuff. Yes, you know the one.

How good am I at playing chess? Pretty mediocre, really. But chess actually has a pretty wide skill range. The professional chess world uses a rating system called Elo. It is just like magic internet points you get everywhere, but it is actually useful. It represents how good you are at playing chess. Simple enough.

I would say somebody who learned the rules of chess is probably rated something like 800-1000. The best players in the world, by comparison, are rated 2500-2800. But how much better is that, really?

Let’s say we have player A and player B. If player A is rated 1200 and player B is rated 1250, I would expect a pretty even game. If A is 1200 and B is 1400, I expect a completely one-sided game. And I expect the exact same one-sided game if A is 1400 and B is 1600. And likewise again if A is 1600 and B is 1800. A at 1600 is much better than A at 1400, but still is easily beaten by B at 1800.

So as a general rule of thumb, you are never going to beat somebody with a +200 rating difference over you in a serious game. There is quite a lot to learn, and chess at different skill levels is almost a different game entirely. Let’s call it a metagame. Suppose A and B are both rated 1600 and they play a game. They keep in mind the same rules and strategies they learned when they were 1400, but then play a metagame on top of the actual game. This meta layer was invisible to them when they were 1400, but learning it was what made them 1600 players rather than 1400 players. It isn’t always clear how to learn what these meta layers are, as you don’t “see” them until you learn them. I think intuition plays a part in this.

I would say that I have chess intuition. Getting better at chess came easily to me. It took time, of course, but it was never hard to learn. In fact, quite the opposite – learning was fun. And chess being fun to learn made me get better at it very quickly. I was yet again biking downhill while learning chess.

But enough about chess. Let’s talk about writing!

You already talked about writing.

Well… yes and no. I said I was good at writing, but what I meant is that I am good at a particular kind of writing. But I am also bad at a particular type of writing. Fiction.

I thought I was good at writing, and I used to read fiction frequently. So I figured, how hard can it be? I should write a book!

That’s when I learned that I hate writing fiction. It is drawing the owl all over again.

You have to create a world from scratch. And characters. And the characters need to have motivations that make sense. And the dialogue needs to feel realistic. The story has to be interesting.

And I just don’t have the intuition to do it.

What should we do about intuition?

What’s the conclusion, then? What should you take away?

I don’t know, to be honest. I haven’t figured that out myself.

All I do know is that in my own life, I am very good at some things and very bad at other things, and the main difference I notice is intuition.

At the end of the day, I am always trying to learn new things. I know how to learn the things I am good at already. I just don’t know how to learn the things I am not good at.

If you figure out, let me know.